Taroko Arts Residency(TAR) Project considers the possibility of practicing contemporary curatorial research from a specific location in one of Taiwan’s National Parks. The project aims to define an alternative imagination of nature, and through a process of co-operation between artists, curator and local residents to redefine relationships between people, environment and artistic practices. The exhibition at TCAC brings an urban ecology into dialogue with these elements.

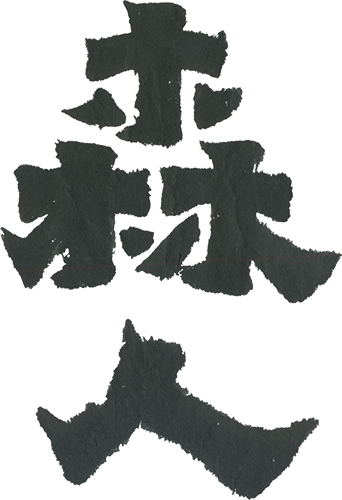

The locations of the curatorial base in Taroko National Park, Datong and Dali, are called dark villages, because they have no electricity supply. Many years ago, Taiwan’s government claimed the area as a national park, forcing local aboriginal communities to migrate to the modern cement houses built at the foot of the mountain. Today only a small percentage of the aboriginal people continue to own their ancestral homes on the mountain. In 2011, Cheng-Tao Chen visited Datong with the Society of Wilderness, and was impressed by both the complexity of its mountain ecology and the tribal leader’s loud, clear singing voice. In 2015, he returned to Datong, bringing with him his artistic project “Tree’s Journey”. He met an aboriginal woman who requested Cheng-Tao to leave “Tree’s Journey” with the tribe so it could be exhibited for future visitors. In exchange, Cheng-Tao was surprised to be given a pair of rose stones in appreciation from the tribe. Subsequently, “Tree’s Journey” was renamed “Stone and Tree”. This experience inspired Cheng-Tao to think about aboriginal people’s aesthetics, and their desire to have an exhibition.

How can we apply the practice of curatorial research in a national park to explore imaginations about the relationship between humans and nature? How should we consider ecology when thinking about the natural environment? In Félix Guattari’s The Three Ecologies it states that we need to consider the mental, the social and the environmental in order to fully realize the definition of nature. Only through trans-disciplinarity and the philosophical process of subjectivity can we think about the crisis ecology faces today. The same conditions apply when art meets nature. It is only through participation – the co-operation between artists and aboriginal community – that positive concepts of nature and the ecology can be generated through art. The definition of participation here is different from that of Nicolas Bourriaud’s relational aesthetics, where he declares it as an artistic form that attempts to resist the artwork as object. Instead, this idea of participation is closely related with Guattari’s views on ‘living together’ in direct response to questions about nature.

Extending the discussion of living together and the ecology of institutional critique, this project creates a dialogue between the distinct sites, displacing the artists’ projects and audience between the two spaces.